Object of the Month 09/2025

The art collection of the Humboldt University comprises a number of special portfolios containing works by students of art education. The former institute at the Humboldt Universität’s Faculty of Education taught art history and art education methodology as well as artistic practice for prospective art teachers. The political goal of educating students to become ‘all-round socialist personalities’ (allseitig gebildet[e] sozialistische Persönlichkeit, Klemm 2015, p. 49) and to ‘implement socialist realism as an art policy doctrine in society’ (sozialistischen Realismus als kunstpolitische Doktrin in der Gesellschaft einsetzen, ibid., 2015, p. 49) was also firmly anchored in this subject. The Department of Art History and Aesthetics at Humboldt University was thus tasked with shaping the new socialist personality through the arts and their scientific and educational accompaniment. Teachers in the field of art education therefore not only had to be artistically accomplished, but also socially engaged (e.g. as leaders of so-called circles in which lay people were instructed in artistic creation) and, of course, committed to Marxism-Leninism in terms of their intellectual and ideological beliefs – after all, they were training future art teachers.

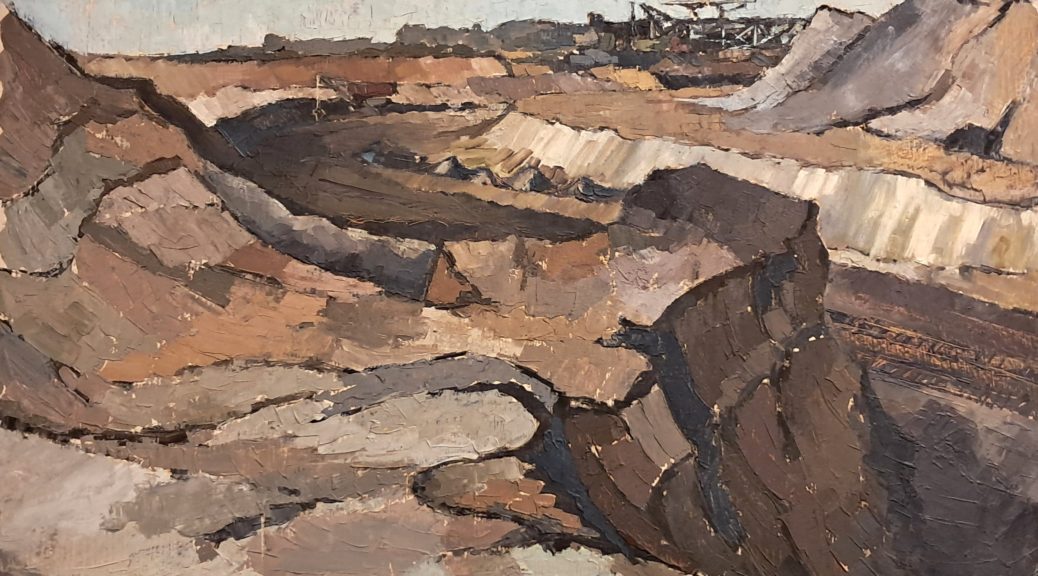

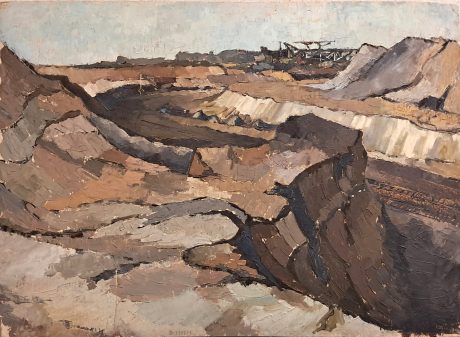

For artistic practice, which was taught at the HU by visual artists (Hermann Bruse, Dietrich Kunth, Johannes Prusko, Gerenot Richter, Erhardt Schmidt, Norbert Weinke, Barbara Müller, Wolfgang Frankenstein, among others), the guidelines were relatively vague. They were to deal with life-affirming subjects, themes such as nature, homeland and the construction of socialist life, and in doing so to try out different techniques and materials. The works on industrial landscapes, recreational and private life, holidays, village views or motifs of the reconstruction of Berlin seem to follow this guideline. There is evidence that printing techniques such as etching, linocut and woodcut were practised, as well as drawing techniques using ink and charcoal and oil painting.

One exemplary group of early works shows the implementation of the curriculum requirements quite clearly: industrial pictures created in the sponsoring company of the HU, the ‘Glückauf’ lignite factory in Knappenrode. Eva-Maria Mancke, a lecturer at the Institute of Art Education in the field of artistic practice, describes this form of ‘active participation in everyday socialist life’ in detail – and probably also somewhat embellished – in an article about the students’ 14-day work assignment:

We found a willingness to help and understanding, and that helped us over many a cliff, because back pain and blisters on the hands are not the pleasant side of a job. Nevertheless, there was no hanging of heads. […] We found our motifs in the factory, in the overburden and on the assembly site, and we drew and painted everything we had already come into contact with during our labour. („Wir fanden Hilfsbereitschaft und Verständnis, und das half uns über manche Klippe hinweg, denn Rückenschmerzen und Blasen an den Händen gehören nun mal nicht zur angenehmen Seite einer Beschäftigung. Trotzdem gab es kein Kopfhängen. […] Unsere Motive fanden wir in der Fabrik, im Abraum und auf dem Montageplatz, und wir zeichneten und malten all das, womit wir während des Arbeitseinsatzes schon in Berührung gekommen waren.“; Mancke 1958, p. 13f.)

Works created after the mandatory multi-day excursions to industrial facilities such as the Glückauf coal-mining factory can be found sporadically among the numerous works of former art education students. The 1951 art education curriculum shows that the subject area ‘Man and Space’ with exercises on ‘spatial projection,’ ‘interior and exterior architecture’ and ‘building complexes’ had to be completed in three academic years.

The actual work assignment was followed by the artistic realisation of the experience. The resulting works were exhibited in the company’s cultural centre and later also at the HU. In particular, prints were produced as gift folders for the inauguration of a new conveyor bridge. The Institute’s lecture activities (‘Miners’ depictions in the visual arts”) and the planned joint visit to the IV. German Art Exhibition in Dresden, the guidelines of the so-called Bitterfeld Way were realised in exemplary fashion. However, the invoked community between artists and workers had already become obsolete in 1965 in terms of realpolitik. The works of the former Institute for Art Education are therefore not only aesthetically but also historically valuable testimonies. Unfortunately, many works dating from the 1950s to the 1980s are unsigned or unidentifiable, so only in some cases can the works be attributed to former students.

Author: Christina Kuhli

Literature:

Über die Veränderungen in der Lehrerausbildung am Institut für Kunsterziehung. Beitrag zur Lehrkörperkonferenz der Pädagogischen Fakultät an der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin 18.12.1958, UA HU, Päd. Fak. 02, 0026, [p. 4];

Eva-Maria Mancke: Studenten arbeiten und zeichnen in der Produktion, in: Kunsterziehung. Zeitschrift für Lehrer und Kunsterzieher, Heft 12, 1958, pp. 12-14;

Wolfgang Frankenstein: Zur Stellung der Kunsterziehungswissenschaft im System Kunstwissenschaft, in: Theoretische Grundlagen der bildkünstlerischen Gestaltung, Wissenschafts-Konferenz des Bereichs Kunsterziehung, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin 1978, pp. 161-169;

Marieluise Schaum: Zinnoberrot und Preußischblau oder die Kunsterziehung an der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Positionen und Potentiale kunsttheoretischer Entwicklungen am Bereich Kunsterziehung der Sektion Ästhetik und Kunstwissenschaften der Humboldt-Universität in den siebziger und achtziger Jahren, in: Wolfgang Girnus/ Klaus Meier (eds.): Die Humboldt-Universität Unter den Linden 1945 bis 1990. Zeitzeugen – Einblicke – Analysen, Leipzig 2010, pp. 467- 494;

Thomas Klemm: ‘Die ästhetische Bildung sozialistischer Persönlichkeiten’. Institutionenelle Verflechtungen der Kunstlehrerausbildung an den Hochschulen der DDR, in: Die Hochschule, 24, 2015, pp. 48-61.