January 30, 2026, 12:15 p.m. – Transcultural Soundscapes – Performative guest lectures in the object lab

Musicians Kimia Bani and Yalda Yazdani are invited to participate in the seminar Echoes Across Borders: Navigating the Musical Tapestry of Berlin’s Migration History. Through performative presentations, the artists and students will explore the topics “The Politics of Musical Participation: An Ethnographic Study on the Situation of Female Singers in Post-Revolutionary Iran” and “Drumming as Feminist Resistance and Political Expression.” The event will take place in English at the Objektlabor (Zentrum für Kulturtechnik, Haus 3, Campus Nord). Please register in advance at wissensaustausch.zfk@hu-berlin.de.

February 6, 2026, 6-8 p.m. – Experiencing Wayang

Join us for an immersive evening exploring Wayang Kulit, Indonesia’s traditional shadow puppet theatre. Discover the meanings and characters behind the puppets, take part in a short storytelling performance, and join a creative workshop inspired by the ancient Hindu epic Ramayana, where you can paint and create your own Wayang figure. The event is organized by students of Humboldt-University as part of the university course Asia in Berlin: Curating (Im)material Heritage.

The event will take place at Haus der Indonesischen Kulturen (Theodor-Franke-Str. 11, 12099 Berlin). Please register at kulturhaus@indonesian-embassy.de

February 12, 2016, 4-6pm – “Blurred tracks”

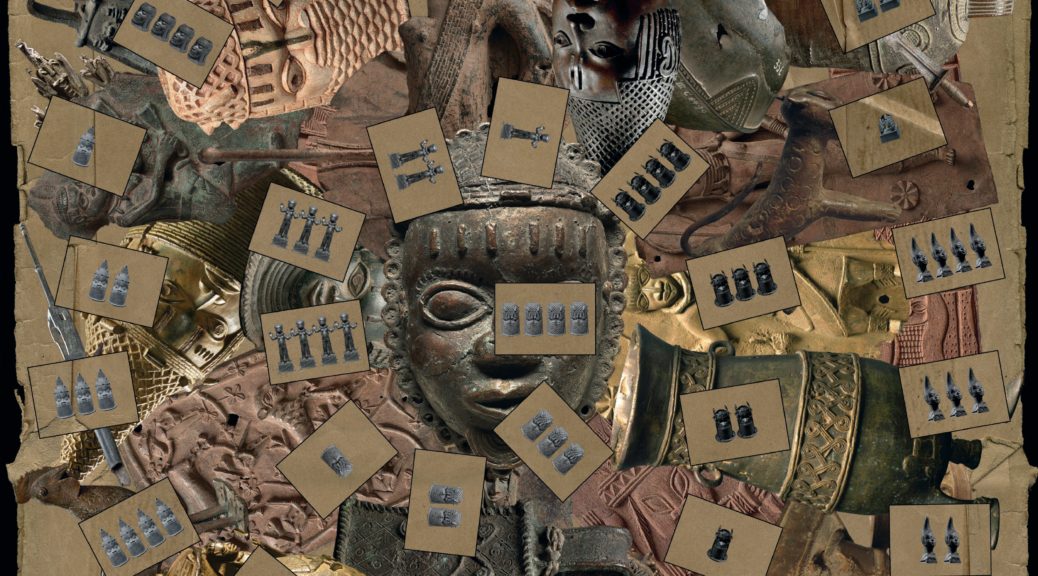

The students of the Berlin Perspectives Course on Law and Decolonization of Cultural Heritage in Europe invite you to an exhibition! The exhibition will display students’ final projects, where they reflect upon issues such as the traces of colonialism in public spaces in Lisbon and Shanghai, the importance of traditional Amazigh music, the misappropriation of Indigenous patterns in fast-fashion, and other contemporary matters that show how decolonization is still an unfinished process.

The exhibition will open from 16:00 to 18:00 at the Object Lab (Zentrum für Kulturtechnik, Haus 3, Campus Nord). Visitors can expect interactive workshops, screenings and thoughtful conversations with the students! Please register in advance by emailing wissensaustausch.zfk@hu-berlin.de.

_______________________________________________________________________

We are delighted that nine seminars will be supported by the ‘Learning and Teaching with Society’ funding programme this winter semester! The seminars will receive seed funding of up to €1,000, as well as content-related advice and methodological support from the Knowledge Exchange with Society competence area.

If you are interested in applying for funding, you can find information about the previous call for proposals here. The next call for proposals will be published on this website soon and will be based on the previous one.

Click on the image below to view a digital version of our programme flyer:

The Seminars in the Winter Term 2025/2026

The seminars focus on learning together with society. In collaboration with artists, cultural institutions, and civic initiatives, students engage hands-on with topics such as migration, cultural heritage, environmental destruction and regeneration, as well as practices of remembering, presenting, and mediating. Central to the program is research-based, transdisciplinary work on socially relevant questions, with an emphasis on diversity, participation, and decolonization.

Together with children, young people, and diverse communities, the students develop performances, exhibitions, workshops, and audio walks. In doing so, they reflect on educational processes and experiment with new ways of learning and teaching both within and beyond the university. The courses aim to co-create learning as a collective, creative, and socially engaged practice.

In the following article, we will provide a comprehensive overview of the available seminars.

About the Nine Seminars:

1. Movement and Learning in Teaching for Primary Schools – circus/dance education and choreography

Bernadette Girshausen (Institute of Sport Sciences) *

In cooperation with the youth group “Showgruppe Altglienicke” and invited guest experts (circus artist, stage technician), a performance based on Lewis Carroll’s “Alice in Wonderland” is created in the style of nouveau cirque. The students are trying out different disciplines and support the young people in developing the show. The performance will be shown in December at Cabuwazi Altglienicke.

Work-In-Progress Show

On 21 November at 4:30 p.m., we cordially invite you to a work-in-progress show at Objektlabor! Please register in advance by emailing wissensaustausch.zfk@hu-berlin.de.

2. Didactics of the German Primary Classroom

Prof. Dr. Petra Anders (Institute for Education Sciences) **

How can students grasp, develop, and discuss relevant theoretical models on reading and literacy development? By involving ZfK based guest artist Irina Demina, BA students engage in holistic, practical experiences in which they approach theories of learning choreographically. Following an apporach of community-based learning, they present their work to fellow students and school teachers opening up opportunities for reflection.

3. Literacy and Media Environments; Theater for Children and Young People

Maike Löhden (Institute for Education Sciences); Dr. Ada Bieber (Institute for German Literature)

In this interdisciplinary collaboration of two seminars, primary school teaching students are sensitized to various forms of theater practice and their application in specific contexts. Together with theater educators from Komische Oper and Gripstheater and with teachers and pupils of Wilhelm-Hauff-Grundschule in Berlin Wedding, the didactic-pedagogical potentials of theater as part of literary and cultural education in elementary school education are discussed and tested.

4. Law and Decolonization of Cultural Heritage in Europe

Dr. Vanesa Menéndez Montero *

The course adopts a transdisciplinary approach grounded in law and human rights to explore and deconstruct colonial legacies in the European cultural sphere. Both theoretical and practical sessions invite active student participation and reflection on how historical injustices have been (mis)represented in European imagery. Artists and experts are invited and indigenous positions integrated as a key source of knowledge. Final projects on decolonial practices will be presented at the Object Lab, ZfK.

5. Documenting Environmental Change: an Exploration into Audio-Visual Practices

Yasemin Keskintepe (Institut für Kunst und Bildgeschichte); Hanna Grzeskiewicz

This seminar explores how artistic practices respond to environmental destruction and regeneration, inquiring into ways of seeing and listening. Focusing on audio-visual projects that trace ecological change and its entanglements with social injustice, we ask how sounding and imaging techniques make destruction perceptible and contribute to regenerative practices. With guest inputs from artists, the seminar creates a transdisciplinary lab through readings, artworks, and discussion.

6. Artistic Responses to HIV/AIDS: Curating Exhibitions in Berlin

Samuel Perea-Díaz *

This seminar offers a critical examination of curatorial practice and exhibition-making in Berlin, with a focus on HIV/AIDS-related cultural production from the 1980s to the present. Through dialogues with artists and curators, and visits to organisations such as Schwules Museum, nGbK, and WeAreVillage, students will gain insights into evolving curatorial practices. Coursework includes the development of a conceptual exhibition proposal on art and HIV/AIDS.

7. Echoes Across Borders: Navigating the Musical Tapestry of Berlin’s Migration History

Dr. George Athanasopoulos (Institut für Musikwissenschaft) *

This seminar explores music and migration in Berlin’s cultural landscape. It includes reciprocal visits and collaboration with the Open Music School Berlin, a project run by the “Give Something Back to Berlin” Initiative, as well as a music-based workshop held at the Object Lab, co-led by musicians Kimia Bani and Yalda Yazdani.

8. Spatial Memory Practices in Berlin: Monuments, Voids, and Voices

Pablo Santacana López, Kandis Friesen *

The seminar explores contested spatial memory through monuments and voids, culminating in student-created audio walks in Volkspark Friedrichshain. Civic partners include Vincent Bababoutilabo (postcolonial memory work), artist Miriam Schickler (sound research), and Cashmere Radio (community radio station). Students collaborate with memory activists and cultural practitioners on site-specific works bridging academia and civil society through transdisciplinary knowledge-making.

9. Asia in Berlin: Curating (Im)material Heritage

Dr Mai Lin Tjoa-Bonatz, Felicitas von Droste zu Hülshoff *

Zusammen mit javanischen Kulturschaffenden wird eine Ausstellung zum Schattenspiel Indonesiens kuratiert. Schattenspielfiguren sind im Haus der Indonesischen Kulturen bis heute ein Bestandteil von Darbietungen. Basierend auf Theorien der Museumskunde und Provenienzforschung vermitteln die Expert:innen dieser traditionellen Praxis die sozio-kulturellen Hintergründe des Puppenspiels. Das Seminar reflektiert, wie diese Inhalte heute im Kontext von Diasporagemeinschaften in Berlin vermittelt werden können.

* The seminars mentioned above will be part of the Berlin Perspectives Programme.

** The seminars will be held in German.

How did you apply the ‘Learning and Teaching with Society’ programme approach to the seminar? In what ways did you engage with questions, knowledge and experiences from society?

How did you apply the ‘Learning and Teaching with Society’ programme approach to the seminar? In what ways did you engage with questions, knowledge and experiences from society?