Object of the Month 09/2023

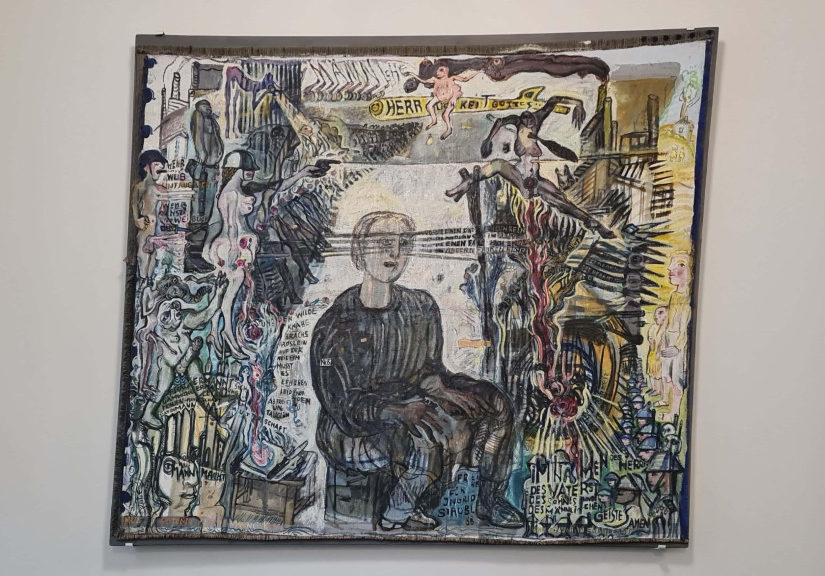

Accusing, shocking, melancholic – the large-format painting by Annemirl Bauer is expressive. From the eyes of a centrally placed female figure, crouching on a box in prisoner’s clothing, rays emanate to both sides of the picture. On the left, a row of naked women in high-heeled shoes stand in line, the one in front holding out her armed hand. Behind her are other figures, some with oversized phalluses. The pistol points to the right side of the picture with a female figure crucified by crutches, from whose womb blood is flowing. A male army, indicated in heads at the lower right edge of the picture is described with the invocation of the Trinity. The dark, violent and sexualised scenes are only counteracted on the far right by a mother and child standing in the golden light, standing upright and calm despite all hostility.

The title “Männliche Herrlichkeit Gottes”, present in the picture through characters in the sky or on a rocket, refers to the horrors of war and violence (perpetrated by men) as well as to the roles of women – as victims, as perpetrators, as mothers.

Since 2018, the painting has been hanging in the Humboldt University as one of the few works by Annemirl Bauer still present in public. The valiant paintress, herself under surveillance by the Stasi, expelled from the GDR artists’ association (VBK) and subsequently banned from working, repeatedly explored feminist themes. The “Male Glory of God” can also be linked very specifically to the conscription law for women in the GDR, the “Women for Peace” (Frauen für den Frieden), but also to the feminist Ingrid Strobl, who was imprisoned in the Federal Republic.

In 1982, a new law on military service was passed that would also have called on women to serve in national defence in the event of mobilisation. Against this, 150 women protested in a joint plea to Erich Honecker: “We women want to break the cycle of violence and withdraw our participation from all forms of violence as a means of conflict resolution. […] We women understand the readiness for military service as a threatening gesture which opposes the striving for moral and military disarmament and allows the voice of human reason to be drowned in military obedience.” (Petition to the Chairman of the Council of State, Erich Honecker, 12 October 1982)

This pacifist criticism was followed by a wave of interrogations by the state security, intimidation and arrests – for example, of the politically active paintress and main signatory Bärbel Bohley, who, like Annemirl Bauer, was organised in the Association of Visual Artists of the GDR (VBK), from whose district executive committee she was expelled in 1983.

Ingrid Strobl, in turn, an Austrian journalist who was editor of the magazine Emma in Cologne from 1979 to 1986, was taken into remand or solitary confinement as a terrorism suspect in 1987. She had been filmed buying an alarm clock that had been prepared by the BKA (Federal Criminal Police Office) and identified in the remains of a bomb in the 1986 attack on the Lufthansa administration building. The attack against Lufthansa, perpetrated by the organisation “Revolutionary Cells” (Revolutionäre Zellen), also had a feminist background and targeted sex tourism (“state racism, sexism and the patriarchy”, as the Revolutionary Cells themselves stated, cf. Ingrid Strobl: Vermessene Zeit. Der Wecker, der Knast und ich, Hamburg 2020). Strobl received public solidarity after her arrest.

Even without knowledge of this historical background, Annemirl Bauer’s work has an effect through its offensive pictorial language, which also plays with religious motif quotations.

Despite all the criticism – especially against the rejection of Annemirl Bauer’s repeated calls for travel “with return” – the artist was not a dissident and did not want to leave the GDR. Changing the social and political structures, that was her struggle throughout her life, which she lost through her early death shortly before the fall of the Wall in the summer of 1989.

Since 2010, a square named after her in Friedrichshain at Ostkreuz station has commemorated the pugnacious artist.

Author: Christina Kuhli