Object of the Month 08/2025

Visibility and invisibility are intertwined in many ways in this work of art. Although it is located in the main university building, it is somewhat hidden away in the lounge in front of the counselling room 2249A. Originally, only a limited university audience could see it, but it was in a place that was closely linked to its history – even though this history was mostly temporary.

The artwork is the result of several art actions from 1983 and 1984, when the artist Erhard Monden and Eugen Blume (then a research assistant at the Berlin State Museums) staged the action ‘Sender–Empfänger’ (Transmitter–Receiver) in the GDR and Joseph Beuys did the same in the FRG, later revisiting the action in a new work. Both the crossing of borders and the expansion of the concept of art gave the action a political dimension – and it was therefore highly suspect for the GDR leadership.

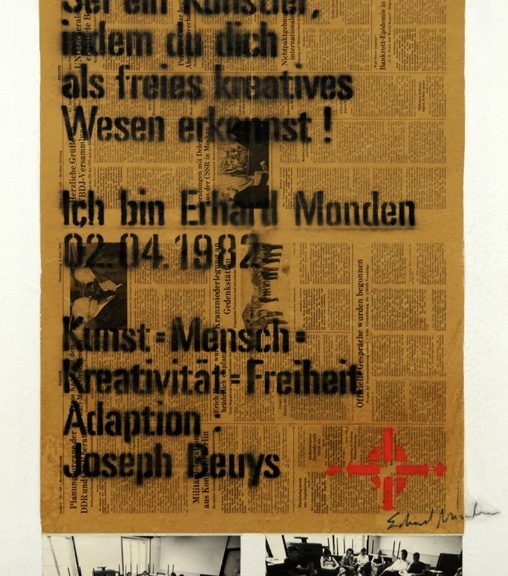

On the last day of the IXth Art Exhibition in Dresden, 2 April 1983, between 12 noon and 1 p.m., a fictitious transmission of information between East and West took place on the Elbe meadows there. Eugen Blume, who graduated from Humboldt University in 1981 with a thesis on Beuys’ concept of art, describes the process as follows: “For the action, I deliberately used the black boards so typical of Beuys, on which I noted the ‘broadcast’ from Düsseldorf. Monden worked with the materials typical of his actions. Three trees served as antennas, to which we were connected by a rope.‘ (Blume 1992, p. 148.) Six blank panels for Beuys’ broadcast and six panels with the inscription „Bestimme dich selbst! Sei ein Künstler, indem du dich als freies kreatives Wesen erkennst! Ich bin Erhard Monden 02.04.1982. Kunst = Mensch = Kreativität = Freiheit. Adaption Joseph Beuys.“ (“Define yourself! Be an artist by recognising yourself as a free creative being! I am Erhard Monden 02.04.1982. Art = Human = Creativity = Freedom. Adaptation Joseph Beuys.”) were displayed. The other boards were also filled with Beuys’ terminology during the course of the action. Monden then redrew his boards. It was an attempt to introduce ’social sculpture‘ in the GDR as well, in a ’parallel action across borders’. It was also a protest against the exclusion of action art from the official art world.

The artist Erhard Monden continued to engage with Joseph Beuys’ art and artistic concepts beyond this campaign. He saw true realism in Beuys’ ‘social sculpture.’ Beuys’ criticism of any form of determination (through production conditions, social constraints) made him suspect not only in the GDR, where he was considered not only an artist but also politically extremely problematic.

From 2 to 8 April 1984, the campaign continued in Berlin with materials from Dresden and discussions. Beuys, who was supposed to be there on the last day, was denied entry – he was ‘considered a dangerous political figure whose influence on the art scene in the GDR should be prevented’ (Blume 1992, p. 149). The mural (stencil spray painting on newspaper and photography) remained a document of this action. It is both double dated (by the date on the newspaper page that serves as the painting surface and the inscription in the middle) and signed (in the centre and bottom right). It conveys a message of self-determination and free creative development against the backdrop of a GDR state that was also restrictive in cultural matters. The connection between art, people, creativity and freedom is explained in the lower third as an adaptation of Joseph Beuys’ beliefs. His works and his credo ‘Every human being is an artist’ were also controversial in the FRG during his lifetime.

The art object was installed in Room 3071 in the main building, which was then used as a lecture hall for art historians, and was thus present during classes held in this room. Although the subject of art history was subject to planned, ideology-driven research, Monden’s art action, which dealt with Beuys’ expanded concept of art, was able to take place unhindered. The work thus also bears witness to the possibilities of an officially Marxist-Leninist art history that nevertheless understood how to keep its eyes and methods open to current scientific discourses.

In 2010, it was removed due to construction work in the main building and reinstalled in the foyer of R 2249 A in 2018.

Author: Christina Kuhli

Literature:

Eugen Blume: Joseph Beuys und die DDR – der Einzelne als Politikum (Joseph Beuys and the GDR – the individual as a political issue), in: Jenseits der Staatskultur. Traditionen autonomer Kunst in der DDR (Beyond State Culture. Traditions of Autonomous Art in the GDR), edited by Gabriele Mutscher and Rüdiger Thomas, Munich/Vienna 1992, pp. 137–154;

Eugen Blume: Laborismus gegen Kapitalismus und Kommunismus im Dunkeln: Joseph Beuys, in: Klopfzeichen. Kunst und Kultur der 80er Jahre in Deutschland, exhibition catalogue Leipzig/ Essen 2002-2003, Leipzig 2002, pp. 45-51;

Christof Baier: “… befreite Kunstwissenschaft”. Die Jahre 1968 bis 1988, in: In der Mitte Berlins. 200 Jahre Kunstgeschichte an der Humboldt-Universität, ed. by Horst Bredekamp and Adam S. Labuda, Berlin 2010, pp. 373–390;

Eugen Blume: Es gibt Leute, die sind nur in der DDR gut – Joseph Beuys 1985, in: Die Unsichtbare Skulptur. Der Erweiterte Kunstbegriff nach Joseph Beuys, ed. by Heinrich Theodor Grütter, Rosa Schmitt-Neubauer et al., exhibition catalogue Essen 2021, Cologne 2021, pp. 217–223;

Mathilde Arnoux: In search of true realism. Eugen Blume and Erhard Monden with Joseph Beuys in the GDR, in: Art studies quarterly 55 (2022), no. 2, pp. 4–13.