Over a period of a thousand years, Chinese girls had their feet bound to shorten them. Europeans looked at this beauty practice with a mixture of fascination and astonishment. In the 19th century, doctors also became interested in bound feet, one of them being the Berlin anatomist Hans Virchow, whose podological collection is now housed in the Centre for Anatomy at the HU.

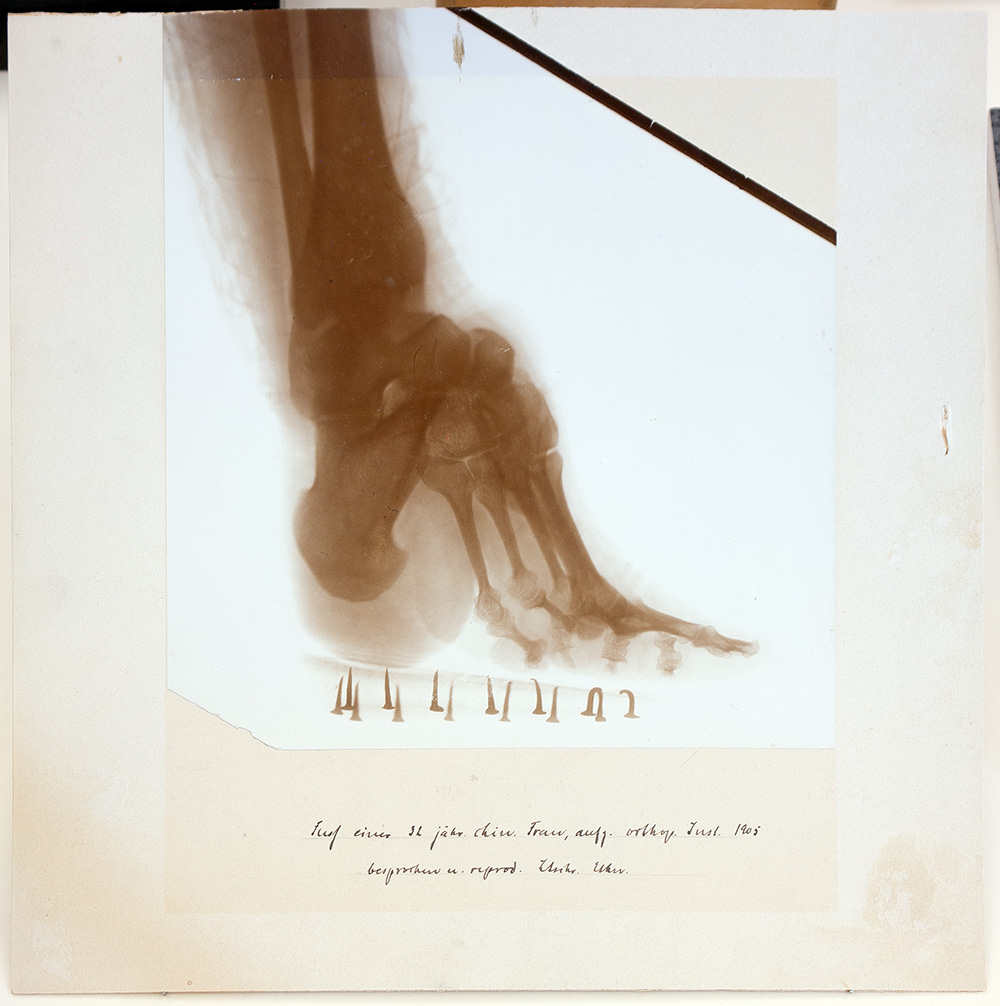

The object presented here, a print of an X-ray image glued to cardboard (cf. https://www.sammlungen.hu-berlin.de/objekte/sammlung-am-centrum-fuer-anatomie/8468/), which is handwritten “Fuß einer 32 jähr. chin. Frau” (“Foot of a 32 year old Chinese woman”), also belongs to this collection.

The skeleton shows the characteristic features of bound feet: the small toes are curved under the sole, the instep is arched upwards. Apart from the extreme foreshortening, the nailed sole is particularly striking – obviously the X-ray image was taken through the shoe.

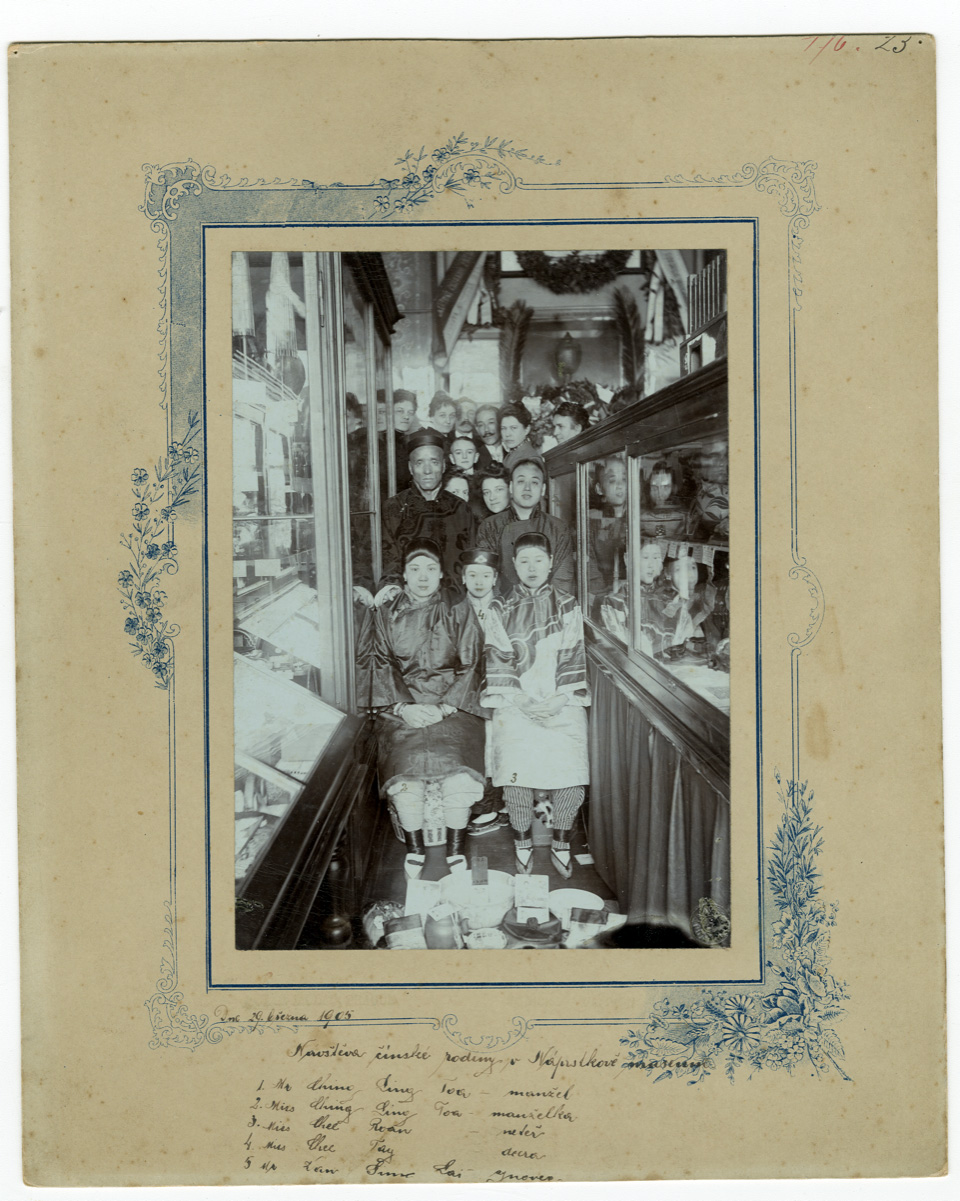

How this came about can be seen in the “Zeitschrift für Ethnologie”: In March 1905, Hans Virchow invited the members of the Anthropological Society to the foyer of the Berlin Circus Schumann “to inspect the Chinese troupe currently staying here” in order to convince himself “of the smallness and reshaping of the Chinese feet”. Advertisements and contemporary sources provide information about the identity of the “troupe”. They were the magician Ching Ling Foo and the “famous small-footed women”: his wife (the “32 year old Chinese woman”), their daughter Chee Toy and Chee Roan, whose name is noted on a photograph in the Náprstek Museum in Prague, another stage of their European tour (cf. Heroldová 2008).

Virchow had already dampened hopes of an inspection of uncovered feet in the invitation, “for it is well known [that] Chinese women are particularly difficult about their feet”. In fact, bound feet were never publicly shown naked in China. Foreign photographers and doctors often broke the gaze taboo in the 19th century by harassing women with money and gifts. Female performers also refused the intrusive gaze, but allowed themselves to be x-rayed – through the shoe. Whether this succeeded, as James Fränkel claimed in the “Zeitschrift für orthopädische Chirurgie” (Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery), only because the women were unaware of the procedure discovered in 1895, or whether he was invoking the topos of the secret “X-ray gaze” here, cannot be decided. In any case, the photograph bears witness not only to the encroaching medical gaze, but also to the resistance of the women.

For the anatomists, the campaign was a success, because it not only allowed them to see the feet in three stages of deformation, but – contrary to the popular prejudice of the inability to walk – also in motion. Virchow made several revisions to the X-ray images for the publication of the examination results: He rotated and retouched the images to make them more legible (cf. Dünkel 2021). For him, the on-site visit was neither the first nor the last encounter with bound feet. As early as 1903, he had examined a wet preparation that had come into the Berlin collection after the First Opium War, and in 1912 he macerated the feet of a woman who had died of typhus, which he had received in the course of the “Boxer War”, the suppression of the Yihetuan movement. Whereas medical practitioners in the 19th century had repeatedly complained about the lack of access to Chinese corpses in addition to the gaze taboo, the situation changed with the establishment of mission hospitals and the colonial wars. Soon almost every anatomical collection of the imperial powers possessed preparations of bound feet – some of them from looted graves. Virchow’s collection of casts, models and bones of bound feet also owes much to colonial conditions. The exhibition “unBinding Bodies” in the Tieranatomisches Theater opposite has set itself the task of re-contextualising these sensitive objects. The focus is not on the feet, but on Chinese women and their lives. The exhibition runs until 31 August.

Jasmin Mersmann and Evke Rulffes

Exhibition

unBinding Bodies. Lotosschuhe und Korsett at TA T

Catalogue

unBinding Bodies – Zur Geschichte des Füßebindens in China

Jasmin Mersmann / Evke Rulffes (Hg.)

transcript Verlag, 2023. Open Access.

Literature

Vera Dünkel (2021): Beyond Retouching. Hans Virchow’s Mixed Media and his X-ray Drawings of the Lotus Foot, in: Hybrid Photography, ed. by Sara Hillnhuetter, Stefanie Klamm, Friedrich Tietjen, London/New York, pp. 79-88.

James Fränkel (1905): Ueber den Fuß der Chinesin, in: Zeitschrift für orthopädische Chirurgie 14, pp. 339-356.

Helena Heroldová (2008): Příběh jedněch botiček, in: Cizí, jiné, exotické v české kultuře, ed. by Kateřina Bláhová and Václav Petrbok, Prague, pp. 126-133.

Jasmin Mersmann (2023): Bis auf die Knochen. Gebundene Füße in anatomischen Sammlungen, in: unBinding Bodies, ed. by ders. and Evke Rulffes, Bielefeld, pp. 119-129.

Hans Virchow (1903): Das Skelett eines verkrüppelten Chinesinnen-Fußes, in: Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 35:2, pp. 266-316 and (1905): Further communications on the feet of Chinese women, in: ZfE 37:4, pp. 546-568.