Object of the Month 02/2026

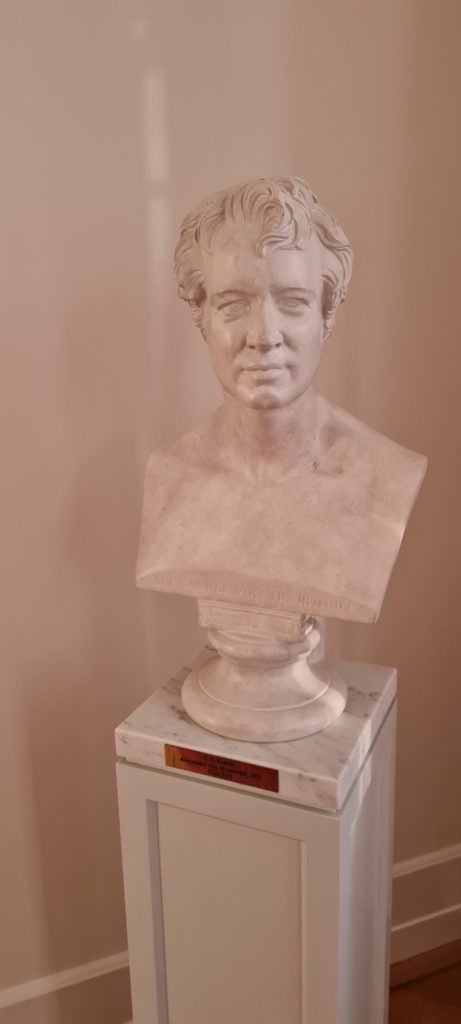

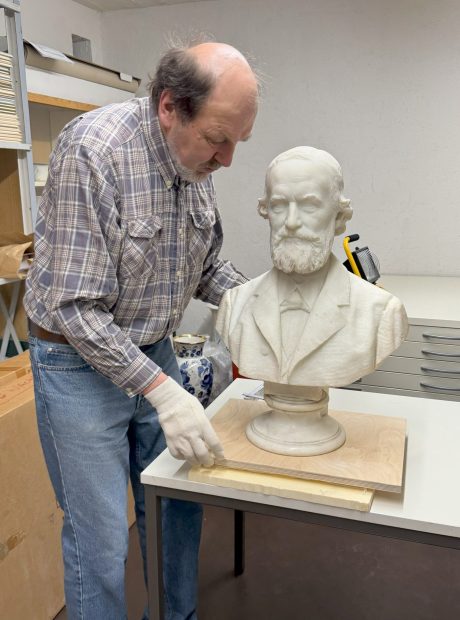

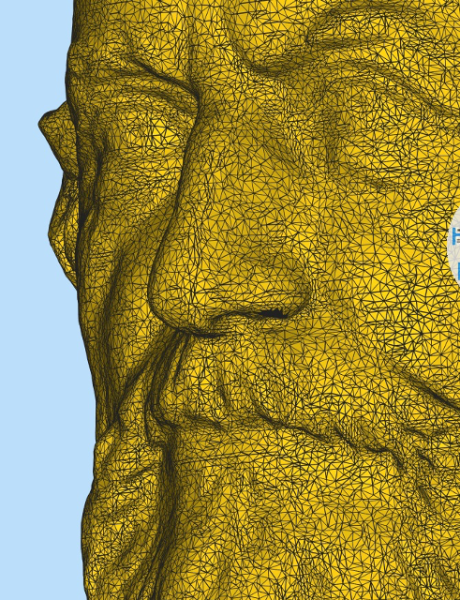

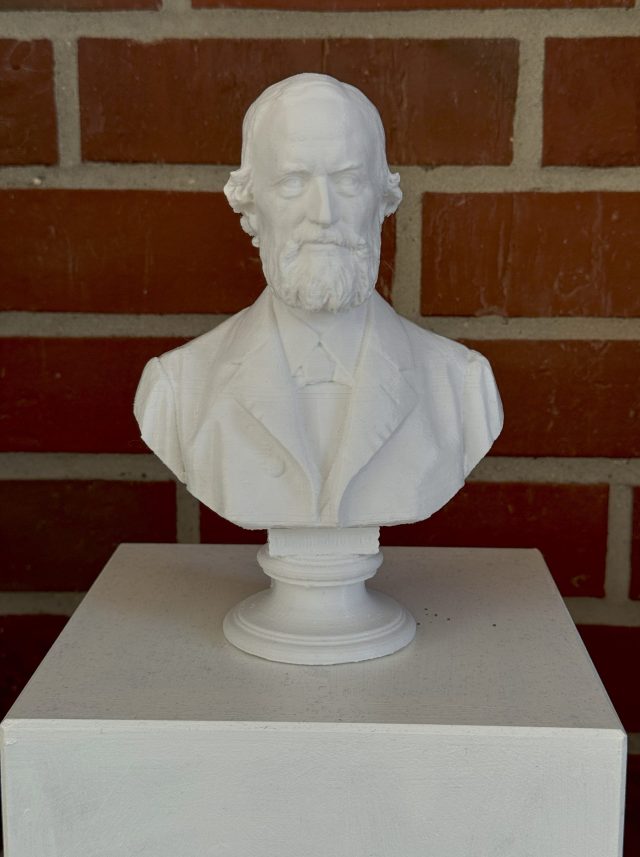

The silver-gilt chain of office bears the portrait of Emperor Wilhelm II in uniform with a Prussian eagle helmet in profile to the right on the front of the medallion, indicating who awarded it. The inscription in the centre of the reverse side also gives the date: ‘Wilhelm II, Emperor and King of the Berlin School of Economics, awarded in 1910’ („Wilhelm II. Kaiser und König der Handelshochschule Berlin verliehen 1910“).

The business school, founded in 1906, ‘established by merchants and intended for merchants’ (as stated in the report on its opening on 27 October 1906), with its focus on business administration, provided a counterbalance to the Seminar for Political Science and Statistics at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität (renamed the Institute for Economic Sciences in 1936), which had been in existence since 1886 and taught and conducted research in economics within the Faculty of Philosophy.

In 1920, the merchants’ guild was dissolved and the Berlin Chamber of Commerce took over the administration of the business school, which was also granted the right to award doctorates in the following years. As a public institution, it was also subordinate to the Prussian Ministry of Trade and Industry. In 1935, it was renamed the Wirtschafts-Hochschule and affiliated with the university. In 1946, it was integrated into the university with the establishment of the Faculty of Economics, which, like the former Handelshochschule, was located on Spandauer Strasse, directly adjacent to the Berlin Stock Exchange.

In contrast to the chains of office of traditional faculties, which cannot be traced at Berlin University, Humboldt-Universität possesses the chain of office of the former Handelshochschule, which has become a faculty or dean’s decoration as a result of institutional changes.

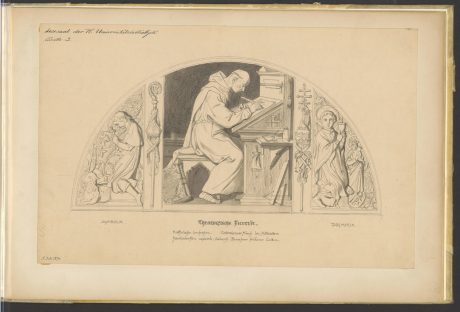

While sceptres have been handed down since the Middle Ages as the most important insignia of universities – they were a sign of the rector’s judicial power and thus of the university’s autonomy – chains of office were uncommon until the 18th century. Occasionally, universities were awarded so-called Gnadenpfennige (pennies, respectively medals of favor) by the ruler as a sign of special privileges. These all bore the portrait of the respective head of state. For the most part, however, they were regarded as jewellery rather than honours. This changed in the 19th century with an overall transformation in the appearance of universities. Nevertheless, at least in Prussia and Bavaria, the king remained the one who decided on the introduction of chains of office. Thus, the profile portrait of Wilhelm II commemorates the Berlin Handelshochschule.

Author: Christina Kuhli

Literature:

Günter Stemmler: Rektorketten – Grundzüge ihrer Geschichte bis zur Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts, in: Jahrbuch für Universitätsgeschichte 7, 2004, pp. 241–248;

Frank Zschaler: Vom Heilig-Geist-Spital zur Wirtschaftswissenschaftlichen Fakultät. 110 Jahre Staatswissenschaftlich-Statistisches Seminar der vormals königlichen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität. 90 Jahre Handels-Hochschule Berlin, Heidelberg et al. 1997;

Ein Halbjahrhundert betriebswirtschaftliches Hochschulstudium. Festschrift zum 50. Gründungstag der Handels-Hochschule Berlin, Berlin 1956.