The poet Adelbert von Chamisso (1781-1838) is probably familiar to most people as the author of the fantastic tale „The Wonderful History of Peter Schlemihl” published in 1814. In it, the protagonist sells his shadow to the devil and thus falls victim to social ostracism. Chamisso’s importance as a natural scientist is far less well known. He was active in the fields of ethnology, zoology and, above all, botany. From 1815 to 1818, he participated in the circumnavigation of the globe by the Russian research vessel Rurik (Chamisso 2012). One of the significant results of this voyage was Chamisso’s discovery of the alternation of generations of the salps. He was not only able to decipher the alternating formation of sexual and asexual generations of these planktonic organisms, but was one of the first researchers ever to recognize the connection between larvae and generational successions of marine animals (Glaubrecht & Dohle 2012).

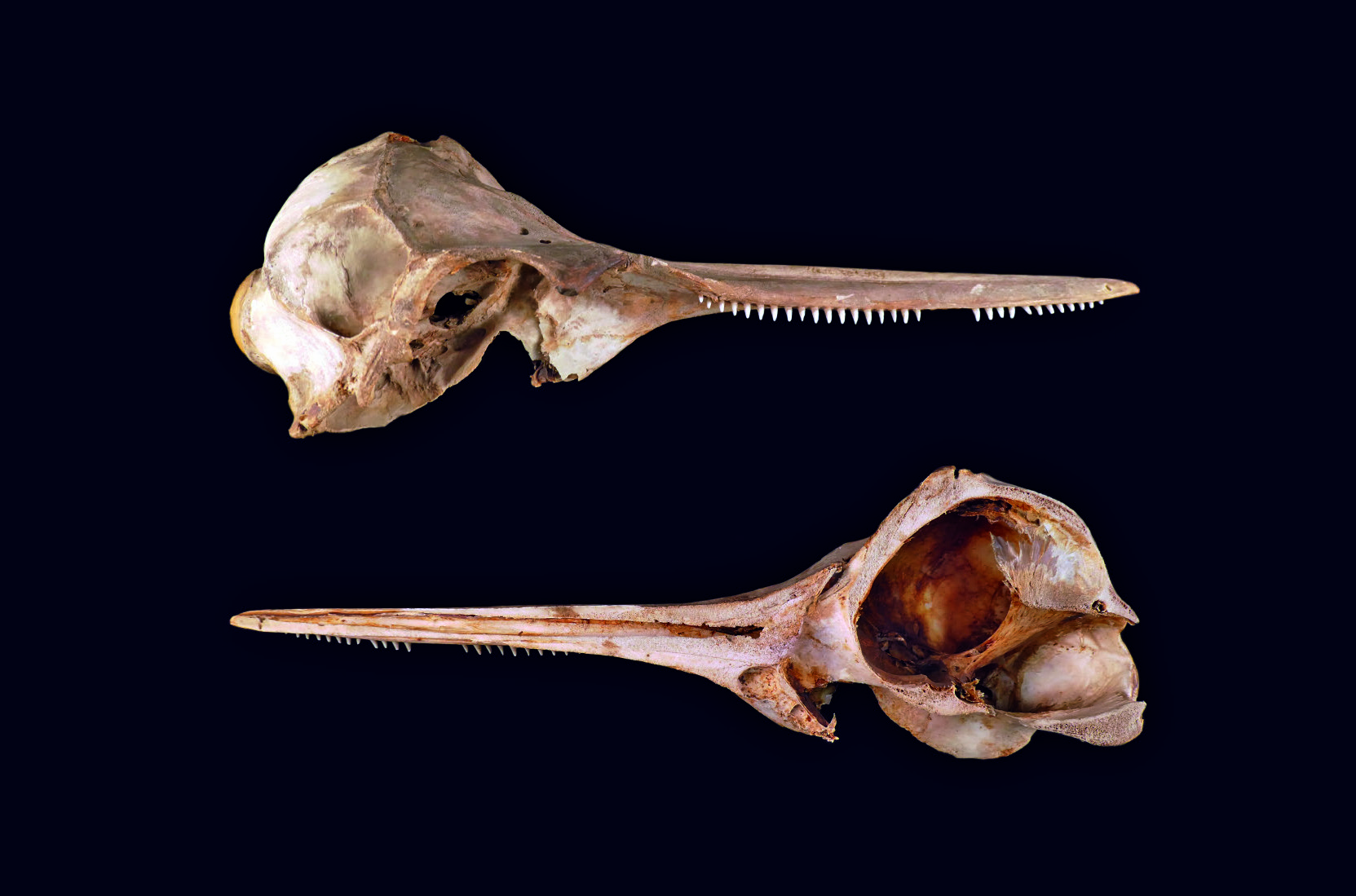

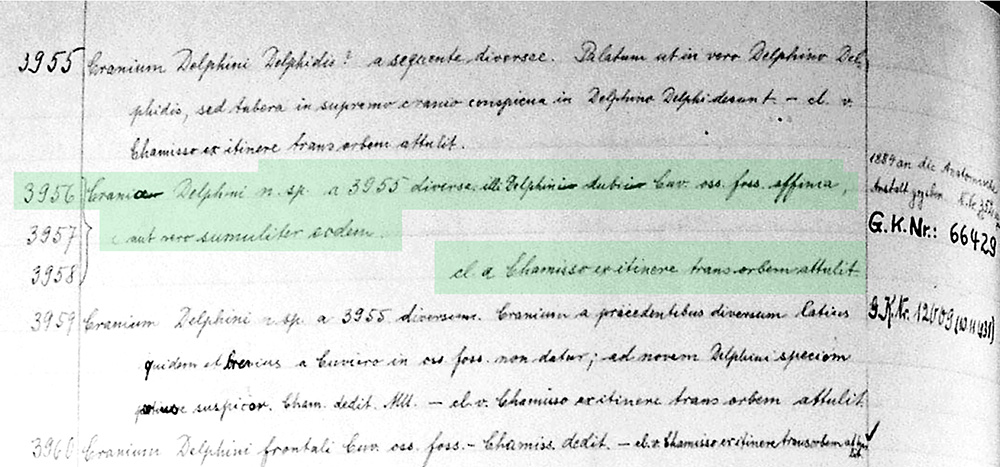

The sawed dolphin skull shown here from two sides also comes from this voyage. In his book “Reise um die Welt” Chamisso mentions dolphins among other things in the notes of May 12 and June 4, 1816: “A dolphin was harpooned, the first of which we got hold of – it served us as welcome food.” “…On the 4th a second dolphin of a different species was harpooned.” In total, Chamisso reports catching of six dolphins, all of whose skulls he donated to the “Zootomisches Museum zu Berlin.” This statement is confirmed by the inventory book of the zootomic collection, as six dolphin skulls collected by Chamisso are listed there. The entry in the inventory book under number 3956 for the skull shown here states: “Crania Delphini n. sp. … cl. a Chamisso ex itinere trans orbem attulit.”

In 1999, the skull and a mandible from the anatomical collection of the Charité were given to the Zoologische Lehrsammlung of the Humboldt-Universität (see Scholtz 2018). The historical significance of these objects went unnoticed for over a decade. It was not until there was an inquiry from Hamburg about the whereabouts of a dolphin skull collected by Chamisso as part of the DFG project “The Appropriation of World Knowledge – Adelbert von Chamisso’s world tour” that our own provenance research led to the identification of the object. Other dolphin skulls collected by Chamisso were identified in the holdings of the Museum für Naturkunde. A comparison with the notes in Chamisso’s travel diaries (Sproll et al. 2023) now offers the possibility to identify individually the six skulls mentioned in the diaries and to which dolphin species they belong.

Like many of his scientifically active contemporaries, Chamisso was a member of the “Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin”. As a characteristic product of the Age of Enlightenment, this private association was launched on July 9, 1773, in the apartment of the Berlin physician Dr. Friedrich Heinrich Wilhelm Martini (Böhme-Kassler 2005). The seven founding members, beyond their professions as physicians, pharmacist, astronomer, royal war councillor and royal administrators, showed great interest in natural science issues and were proud owners of natural history collections. Martini, for example, who initiated the foundation, was a dedicated conchologist, and the pharmacist Marcus Élieser Bloch was interested in ichthyology. The eventually twelve full members met regularly in their private residences, discussed natural history issues, and presented their newly acquired collection items. Associate and honorary members were also appointed. Last but not least, the founding of the Berliner Universität in 1810 caused the number of members to rise sharply. When Chamisso was elected to the GNF in 1819, it was already good manners to list membership alongside that in other national and international associations and academies. The explosive development of scientific research in the 19th century was also reflected in the GNF. It grew steadily, and especially the large number of outstanding researchers who belonged to it shows its historical importance. The focus of interests changed more and more towards biological questions. Accordingly, the Society was closely connected with the Museum für Naturkunde, and with the beginning of the 20th century the meetings were held there. The 2nd World War led to a break in the activities of the GNF.In 1955 the revitalisation took place at the newly founded Freie Universität in the western part of Berlin, where the society is still located today. From the beginning, the GNF has dedicated itself to the promotion and dissemination of scientific knowledge. It still follows this ideal today. It is closely connected to the major Berlin universities and the Museum für Naturkunde. It awards an annual prize for outstanding biological bachelor’s and master’s theses. Regular meetings with scientific lectures as well as excursions are still held. It is the oldest still existing private natural history society in Germany. The GNF celebrates its 250th anniversary on July 9, 2023 with a colloquium in the lecture hall of zoology at the Freie Universität Berlin. In addition, a Festschrift published on behalf of the steering committee highlights aspects of its long history (Scholtz et al. 2023).

By Prof. Dr. Gerhard Scholtz

Links

Zoologische Lehrsammlung der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (only in German)

Salpen (Feuerwalzen), Feuchtpräparat (only in German)

References

Böhme-Kassler, K. 2005 Gemeinschaftsunternehmen Naturforschung. Modifikation und Tradition in der Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin 1773 – 1906. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart.

Chamisso, A. von 2012 Reise um die Welt (Nachdruck). Die Andere Bibliothek, Berlin

Glaubrecht, M. & Dohle, W. 2012 Discovering the alternation generations in salps (Tunicata, Thaliacea): Adelbert von Chamisso’s dissertation “De Salpa” 1819 its material, origin and reception in the early nineteenth century. Zoosystenatics and Evolution 88: 317-363.

Scholtz, G. 2018 Zoologische Lehrsammlung (Zoological Teaching Collection). In: Beck, L.A. (Hrsg.). Zoological Collections of Germany – The animal kingdom in its amazing plenty at museums and universities. Springer, Berlin, pp. 123-134.

Scholtz, G., Sudhaus, W. & Wessel, A. (Hrsg.) 2023 Festschrift zum 250-jährigen Bestehen der Gesellschaft. Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin 57 (NF): 5-320.

Sproll, M., Erhart, W. & Glaubrecht, M. (Hrsg.) 2023 Adelbert von Chamisso: Die Tagebücher der Weltreise 1815-1818, Edition der handschriftlichen Bücher aus dem Nachlass. Brill/V&R Unipress, Göttingen.