Object of the Month 12/2023

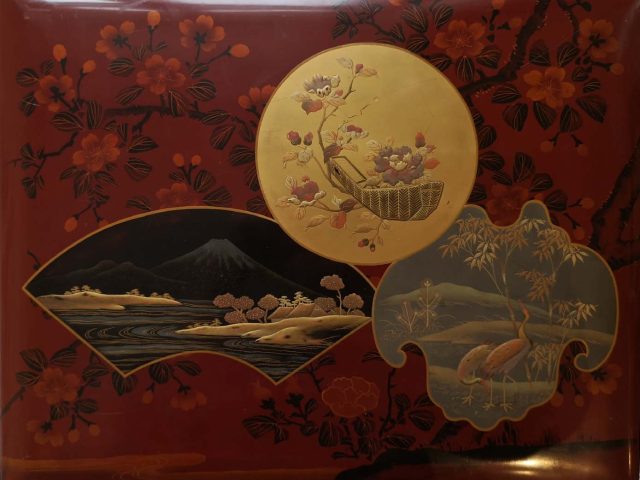

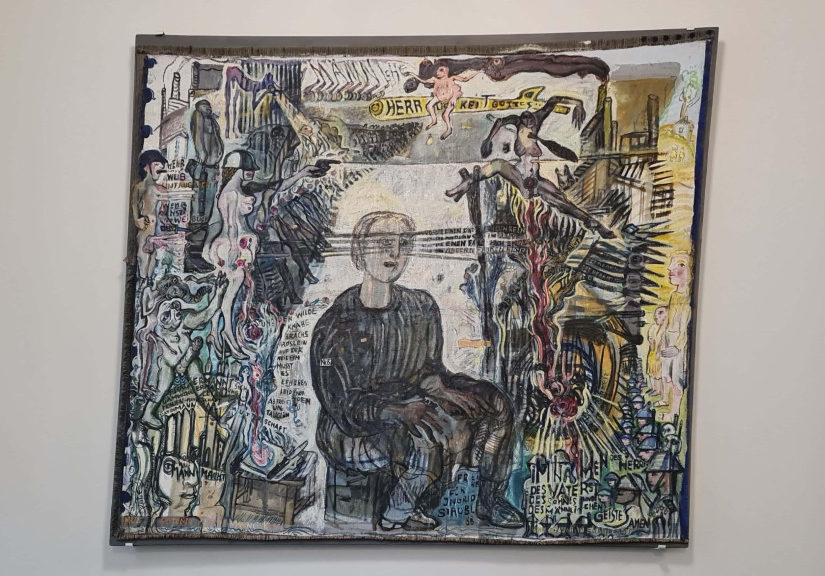

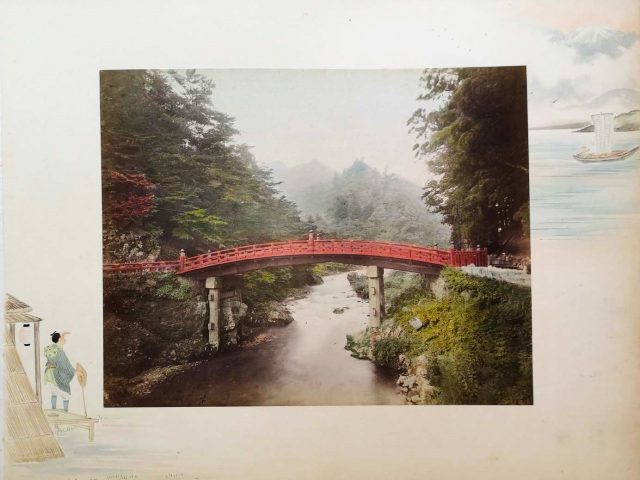

It is preserved in the scientific collection “Holdings of the Mori-Ōgai Memorial Center” and is currently being digitized in the media library of the Grimm Center. Fifty coloured albumen prints are mounted on the large-format pages, framed by illustrations lovingly executed in watercolours.

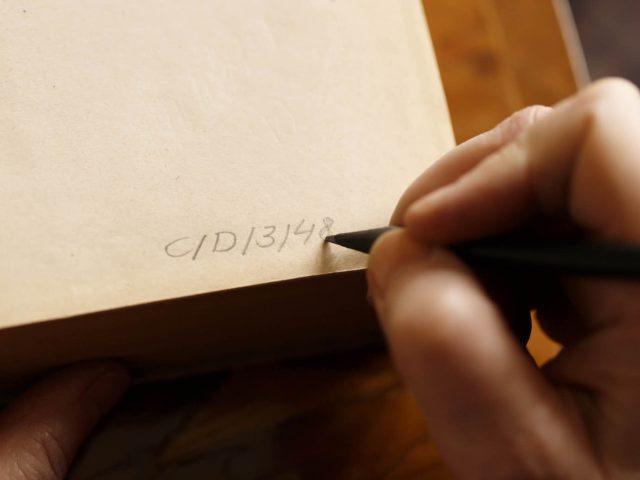

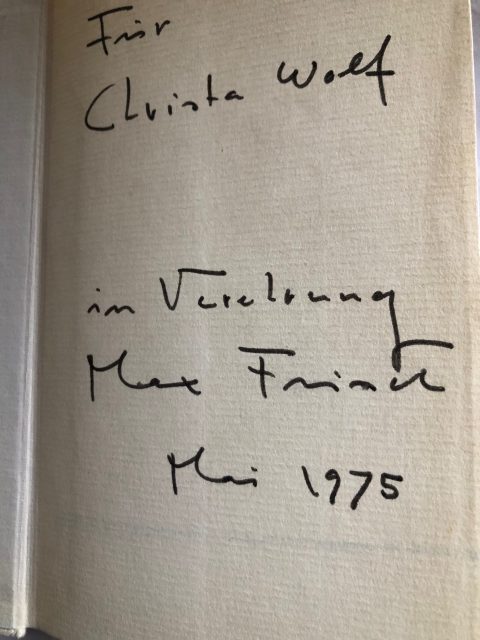

There is no information about the authors of the photographs or their age. It is not known when and how the album came to Europe. The only clue is a delicate entry in pencil on the otherwise blank third page. It reads “Farsari” and thus assigns the object to “Yokohama photography”, which was in demand worldwide at the end of the 19th century.

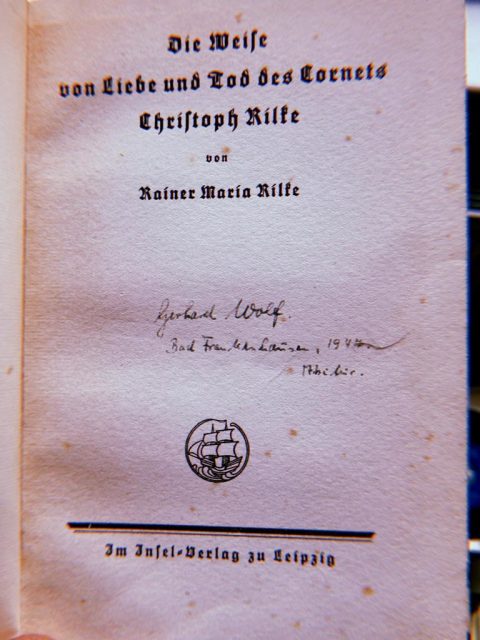

In the middle of the 19th century, the dynamics of global history had also torn Japan from its “idyllic silence” (Mori Ōgai). After more than two hundred years of self-imposed isolation, the island kingdom opened up to the scientific and technological civilisation of the “West”. Although the tourist discovery of the distant destination was initially difficult, the “Land of the Rising Sun” quickly became a new place of longing for the travelling classes of Europe. Aesthetic currents such as the flourishing Japonism and a zeitgeist increasingly critical of civilisation worked together to passionately imagine the popular destination.

Nach dem Frühstück steigen wir zu den Tempeln empor, über lange Stufenreihen in rauschenden Hainen, durch deren dunkles Laub das Meer hindurchleuchtet. Was Griechenland einmal war aber nicht mehr ist, was man [ … ] von seiner Schönheit träumt, das ist in dieser Landschaft zur Wahrheit geworden.

After breakfast we climb up to the temples, over long rows of steps in rustling groves with the sea shining through the dark foliage. What Greece once was but no longer is, what one dreams [ … ] of its beauty, has become the truth in this landscape.

(Harry Graf Kessler, Diary, 15 April 1892)

As early as the 1860s, European and Japanese photographers had studios in Yokohama – the port city that most travellers used to arrive and depart from. The studios mainly produced for tourists, who purchased individual prints or artistically crafted albums. Felice Beato (1832-1909) is considered the founder of “Yokohama photography”. In the early years of his Japanese creative period, the Italian-British photographer captured impressions of a seemingly magical world that had supposedly barely been touched by Western civilisation. His studio popularised the production of prints on albumen paper. His students and competitors – including Adolfo Farsari (1841-1898) and Tamamura Kōzaburō (1841–1932) – responded to the rapidly growing demand. Initially, genre paintings, and later also coloured landscape views, came onto the market.

The employees who skilfully added colour to these prints brought with them skills from the production of woodcuts. Thanks to the cost-effective process, which delivered detailed and attractive results, tens of thousands of copies were soon being produced and sold overseas every year.

Photography and tourism enjoyed a fruitful interrelationship. Travellers at the end of the 19th century were familiar with images. They formed longings and expectations; they defined what was worth seeing. The demand from Europe and North America, which had been preceded by a lively reception of Japanese woodblock prints, in turn exerted a great influence on the choice of motifs, perspectives and colours. By choosing from thousands of images, tourists were able to compile an album of ‘their’ experiences as souvenirs.

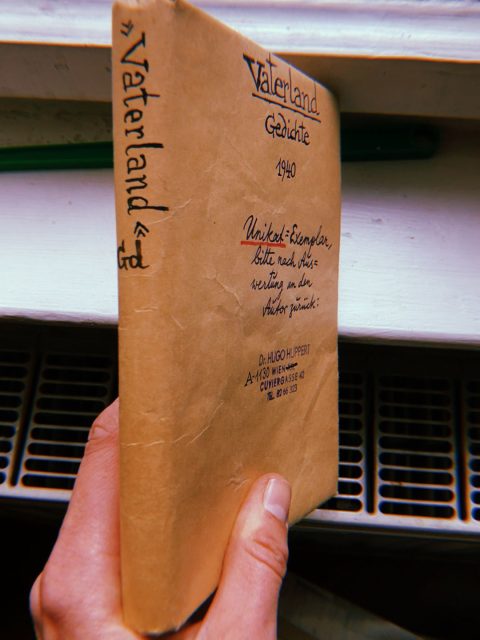

The donation mentioned at the beginning is thanks to a private collector and was made in 2021 in memory of the private banker Moritz Friedrich Bonte (11 July 1847 Magdeburg – 18 July 1938 Berlin). The twelve albums and a total of more than 700 photographs form a valuable source for the work of the Mori-Ōgai Memorial Center, which focuses on the diversity of encounters between Japan and Europe during the transition to modernity. The “Souvenir from Yokohama” and a selection of photographs will be on display in a special exhibition at the Memorial Center from the beginning of 2024. Tokyo Views prepares for the anniversary of the Tokyo-Berlin city partnership next year and looks at the tourist perception of the Japanese metropolis at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. It explains contemporary concepts of sightseeing and presents a series of “notable places” (meisho).

Author: Harald Salomon

Scientific director of the Mori-Ōgai Memorial Centre

The information on the photographs was compiled by students of the Institute of Asian and African Studies.

Mori-Ōgai Memorial of the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

Luisenstr. 39, 10117 Berlin

Phone: 030-2093-66933

E-Mail: mori-ogai@hu-berlin.de

Website: https://www.iaaw.hu-berlin.de/de/region/ostasien/seminar/mori

Opening hours: Tuesdays to Fridays 12pm – 4pm; Thursdays 12pm – 6pm